Dr. Ken Stanley and the Myth of the Objective (Part II)

June 1, 2015

Continuation of this series’ part one about Ken Stanley’s new book, Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective

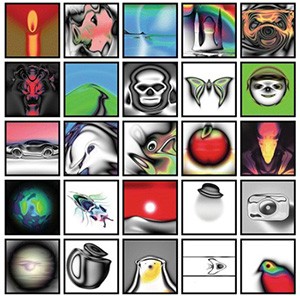

A selection of compelling images discovered on Picbreeder. The lineage of every image in this gallery traces back to a randomly generated blob.

“If you’re not where you thought you’d be, then you’re probably doing something right.”

The UCF College of Engineering and Computer Science professor has propelled the evolution of this idea from algorithms in the lab to wide-scale social implications. Stanley’s newly released book, co-authored with Joel Lehman, a UCF Ph.D. graduate who studied under Stanley, sparks a discussion questioning the closely held assumption that every accomplishment comes from an objective.

What he calls an observation about how things work, the theory born from Stanley’s artificial intelligence research turned out to apply to nearly any field where a specific objective can sometimes hinder progress: biology, sociology, psychology, economics, history, business, entrepreneurship, innovation, education, and so much more. Referencing the applications he and Lehman discuss in their new book, Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective, Stanley explains, “The word ‘accountability’ has seeped into the culture to such an extent that we’re afraid to let anyone do anything where we don’t know where they’re going to end up. And in those cases, we’re making a mistake by thinking that objectives are a security blanket that will protect us from risk.”

Nothing in his background hinted at his current reality. How did an artificial intelligence researcher end up writing a book so far-reaching that a woman would call Stanley, after hearing an interview with him on the radio, asking “how much do you charge?” for talking to her grandson about his life goals?

People often say that a particular pursuit is not “well-defined” enough unless you can tie it to an objective. That’s usually the only way to prove your idea is worth considering. For example, even if you have a strong hunch that combining two chemicals will lead to an interesting reaction, hardly any scientist will take you seriously unless you can define what that interesting reaction would be. Only then could you say that you have a clear objective, and a legitimate pursuit is underway.

Sometimes a word other than “objective” might be used, but usually it plays a similar role. For example, scientists often demand hypotheses from each other because they don’t want to fund research only because it sounds “interesting.” “What is the hypothesis?” they’ll insist. It’s similar to asking what is the objective. Without a hypothesis, an experiment is reduced to mere speculation, little more than child’s play. The hypothesis, like the objective of any project you might want to pursue, certifies that it’s worth pursuing. Even if it might not work out, it still provides a clear outcome that will allow people to judge your success or failure later.

— Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective

When first joining UCF as a professor in 2006, Stanley established EPlex, the evolutionary complexity group that researches the evolution of algorithms as artificial counterparts to human brains—but far below the power of the real thing. These algorithms, basic computer programs, he explains, are inspired by the process of evolution in nature. One of these algorithms is designed to be able to evolve what could be called artificial brains inside of a computer. “NEAT, an acronym that stands for neural evolution of augmented topologies, which sounds like a mouthful, is an algorithm I developed when I was in graduate school,” Stanley says. NEAT’s ability to generate neural networks (artificial “brains” in a computer) that evolve over successive generations, or iterations, then led to the website that inspired ideas in Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned, Picbreeder.

The picture-breeding website allows users to evolve meaningful images from randomly generated blobs by choosing an image in each generation from which to create child images. As the process repeated over and over, users created images of everything from butterflies to space ships. A user can branch off of a picture of a butterfly or create it from scratch, and breed it into an airplane by selecting parents that look like airplanes. Interestingly, users who created the most realistic images were those who didn’t have an objective in mind, and followed opportunities of random images with potential for any recognizable final product instead.

“After years of people playing with Picbreeder—so huge amounts of data—we discovered that the most interesting discoveries, the best discoveries on the site, you could say almost all of the interesting discoveries were made by people who were not looking for them, who were not trying to create those things. For instance, someone evolved a butterfly, but it’s not true that everybody along that chain was trying to evolve a butterfly. Many people were not, and hadn’t even been thinking about butterflies. We found that this principle applied broadly to just about everything on the site,” he explains.

The inspiration behind a successful new search algorithm and the book began with Stanley’s own serendipitous discovery on Picbreeder. Branching from an alien face image bred by a previous user, he intended to breed more alien faces. But like it had for many users before him, serendipity of random mutations caused a new image to form.

Stanley recalled breeding the car, saying, “I was the first person to discover a car, is what inspired everything. None of this theory would exist if I hadn’t bred that car. Because the thing about the car was that I was not trying to breed a car, and that was really preoccupying me because it seemed so contradictory to everything I’d learned in my education about how achievement works.”

As he and Lehman discuss in Why Greatness Cannot be Planned, the story would be merely an interesting anecdote if not for the fact that almost every attractive image on the site follows the same story of serendipity. There is always a surprise stepping stone leading to an unexpected discovery.

Noticing this trend, the authors realized its strange and surprising moral: If you want to find a meaningful image on Picbreeder, you’re better off if it is not your objective.

The paradoxical aspect of the Picbreeder system was confirmed when its researchers ran a powerful computer program for thousands of generations. First choosing a target image from those that users discovered and published on the site, the program began with random blobs as users on the site do, but choosing parent pictures in each generation that look increasingly similar to the target image.

The stepping stones rarely resemble the final products. The images on the left are stepping stones along the path to the images on the right, despite their dissimilar appearances.

“It was, to me, a real shock to see this because I’ve been taught in school, basically my whole life, that the way to achieve something is to optimize toward it, try to get toward it,” he recalls.

To Stanley, this was a revelation that, in some cases, the best way to get to something is to not be trying to get to it. “The more I thought about this the more I realized that this principle makes a lot of sense. I mean, it’s just rational,” he began. “Because how could you know how to get to something new, even if you wanted to? If you were trying to do something really hard, it’s probably true that you will go in the wrong direction first because you have no idea what the right direction is.” In computer science and in life, unleashing search from the trap of the objective, liberating it from the requirement to move only towards where we hope to arrive, allows it becomes a kind of treasure hunter that finds needles in the haystack of what’s possible.

The images and unexpected concepts unveiled by Picbreeder are a link in a chain of discoveries by Ken Stanley and his team at UCF.

>>Written by Lisa Bottomley